The Birmingham Back to Backs

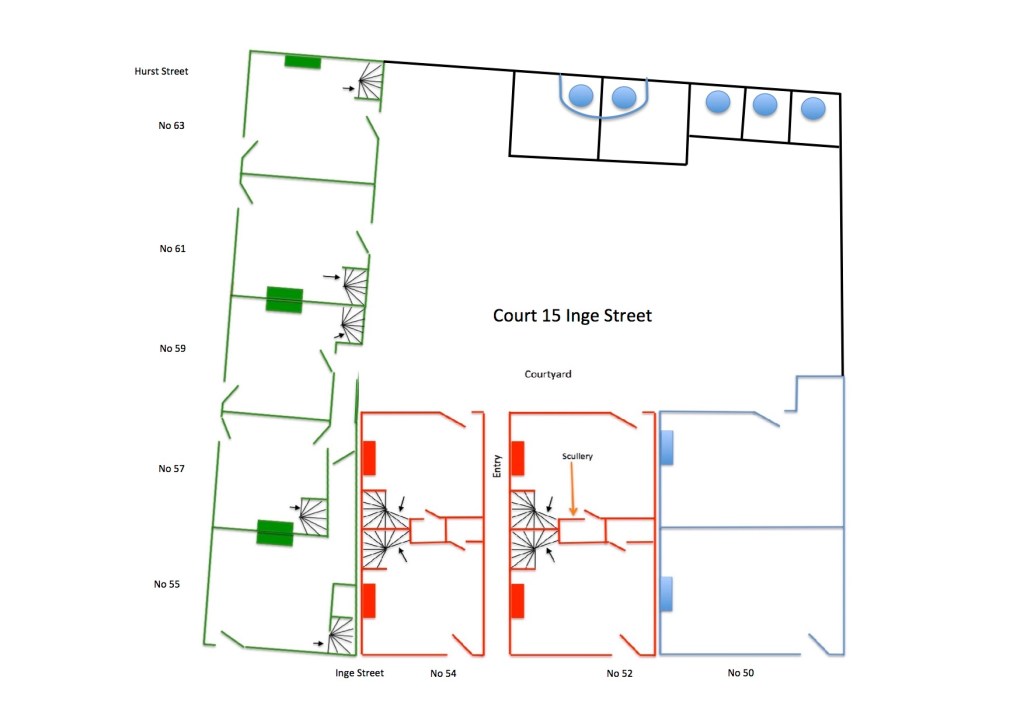

Located on the corner of Hurst Street and Inge Street is the Birmingham Back to Backs. This court, at 50–54 Inge Street and 55–63 Hurst Street, is now operated as a historic house museum by the National Trust. The property opened in July 2004 and has continued to be one of the most successful tourist attractions in Birmingham

The Birmingham Back to Backs (also known as Court 15) are the city’s last surviving court of back-to-back houses. They are preserved as examples of the thousands of similar houses that were built around shared courtyards, for the rapidly increasing population of Britain’s expanding industrial towns. They are a very particular sort of British terraced housing. This sort of housing was eventually deemed unsatisfactory, and the passage of the Public Health Act 1875 meant that no more were built; instead terraced houses took their place. Numerous back-to-back houses, two or three storeys high, were built in Birmingham during the 19th century. Most of these houses were concentrated in inner-city areas such as Ladywood, Handsworth, Aston, Small Heath and Highgate. Most were still in quite good condition in the early 20th century but, by the early 1970s, almost all of Birmingham’s back-to-back houses had been demolished. The occupants were rehoused in new council houses and flats, some in redeveloped inner-city areas, while the majority moved to new housing estates such as Castle Vale and Chelmsley Wood.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs History

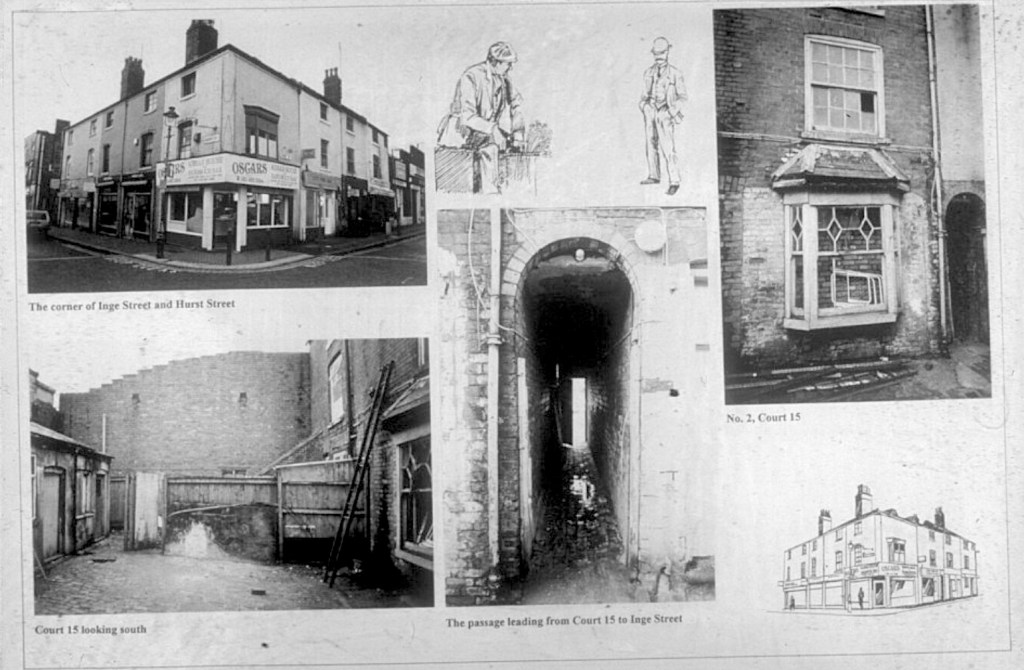

At the corner of Hurst street and Inge Street, facing what is now the Hippodrome and what was the Tivoli Theatre before it, stands a unique collection of houses. Earlier maps have simply called it “Court 15 Inge Street”.

For close on 200 years Court 15 has stood still, while history and Hurst Street progressed around it. It has been the home to perhaps 3,000 people, until, in the 1960’s, legislation meant it could not be called home any longer. The homes were classed as unsanitary, having no indoor bathroom or toilets, therefore the residents were moved out, offering them alternative accommodation in and around the Birmingham area. The majority of residents were not happy with this arrangement, being perfectly happy sharing their toilets and washing facilities with their neighbours, but to no avail, eventually all residents of Court 15 were moved out. The shops and businesses which occupied the front houses, which faced the street carried on with their trade in to 2001, it was ironic that after two centuries of Jewish tailoring in Hurst Street the last man to ply the trade there hailed from the Caribbean.

What makes Court 15 so special? For one thing it represents one of the last survivors of what was once the commonest form of housing in the Midlands and the North of England. For the whole of the 19th Century the back to back court was the most economical and practical solution to working class housing. The courts spread through the inner cities of the industrial Midlands and North occupying every vacant lot, factory wall or redundant back garden. By the First World War, forty years after it stopped building them, Birmingham still had 43,000 such houses, accommodating more than 200,000 people.

The back to back house was a 19th century response to a specific housing need. The houses were only one room deep, with a single entrance ether from the street or from a inner yard. Such houses were “one up and one down” or “two up and one down”. The ground floor served as an all purpose space for living, combining the functions of a living room, kitchen, bathroom and dining room and sometimes a workplace. The upper floor or floors were used as bedrooms, often divided by flimsy panelling or a curtain or blanket hung over a piece of string, to separate parents from children, or tenants from lodgers. Cellars were generally used as a coal storage or a workshop. During the Second World War many cellars were used as Air Raid shelters.

As the name suggests the back to back shared a spine wall with another house facing in the opposite direction, and the most common pattern is of a row of houses fronting the street, with a back row facing into the inner courtyard. This arrangement of the court meant the average house was hemmed in on three sides by other houses, interspersed in a row of houses was an alleyway or entry to give access to the rear yard and back houses. A one room house might be called a “blind back”, shut off by a windowless wall to the rear. This form of housing were usually built against a high brick or factory wall regardless of what that factory was producing.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs Footprint

The present court consists of three pairs of back-to-back houses on Inge Street and a terrace of five blind back houses on Hurst Street, in the form of an L-shaped footprint. All the buildings are three storeys tall with one room on each floor No. 50 Inge Street/1 Court 15, the first to be constructed, is the tallest and the largest in the court. Some evidence exists to indicate that it was originally a single dwelling but it has occupied for most of its life as a pair of back to backs. Evidence to show that it may have originally been one house is available through the layout of the attic. The attic runs across the whole depth of the pair of houses, but was never divided and can only be reached from the back house of No. 1 Court 15 where the surviving staircase is of much better quality than any remaining in the other houses in Court 15. On the second floor, there is a now-blocked doorway in the spine wall between the two houses indicating that the floors to both houses were both accessible. At this level too, No. 50 Inge Street has been split into two rooms by a partition wall. The smaller of the two rooms is unheated and lit by a casement window. There are two tall chimney stacks, one for each house, in the pair.

The tunnel entrance to the court runs between No. 52 Inge Street/2 Court 15 and No. 54 Inge Street/3 Court 15. Each pair of houses shares a single chimney set on the ridge of the roof. The two back houses each have a bay window to allow more light into the ground floor room. The lower floors to these houses have been divided by two spine walls. The upper floors are divided by one spine wall.

In No. 52 Inge Street/2 Court 15 only one original stairway remains — from the ground to the first floor in the front house. The stair in No. 54 Inge Street had been removed at ground floor level but in No. 3 Court 15 the complete staircase survives.

The rear entrances to Nos. 55, 57 and 59 Hurst Street are accessed through a very narrow tunnel entry from Court 15. A staircase on the back wall of each house led up to the first and second floors. The houses were lit by windows on the Hurst Street side and heated by shared chimney stacks. No. 63 Hurst Street shared a chimney with No. 65 Hurst Street, the front house of a pair of back to backs which were part of Court 2 Hurst Street, now demolished. No. 55 Hurst Street has a large bay window at first floor level overlooking Inge Street, which is an early feature. All the houses in the terrace have late 20th century shop fronts, replacing earlier ones which were installed about 1900.

Court 15 may have originally had a water pump in the courtyard, though this is not known for certain. By the 1880s, a single tap would have been installed. The brick paved yard contains an open drain running in front of the three back houses. Two washhouses and outdoor privies were constructed in the courtyard and there were workshops built over the washhouses.

From the late 19th through to the 20th century the buildings have been put to varied uses as retail outlets and workshops. Some of the houses were still occupied as dwellings, until 1966, when the court was condemned along with all the others in the city, and the tenants were rehoused by Birmingham City Council. Because of the nature of the commercial tenancies on Hurst Street, Court 15 escaped demolition.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs Pre Restoration

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs Rescue

Britain’s social policy shifted radically in the 20th century, making what had once been the commonest form of working class houses became the rarest. That alone was probably sufficient to ensure that the court was listed as a Grade 2 building in 1988.

In 1995 the City of Hereford Archaeology Unit was commissioned to investigate the properties in Inge Street. The survey, together with research by the conservation team of the City Council, served to show what a unique and remarkable building Birmingham had on its hands. Listed status saved Court 15 from immediate demolition, but could it stop the progress of time and decay

By the 1990’s Court 15 was deteriorating fast. There were holes in the roof, pigeons in the attic and feral cats in the cellars. The stairs, never particularly safe in the first place, were becoming highly dangerous. it was at this point that Birmingham Conservation Trust stepped in to preserve the houses, reverse the decline and turn Court 15 into one of the most unique museums in the country. The first stage was to buy the freehold from the Gooch Estate.

The family history of thousands of British people seemed to be enshrined within these walls. It is thanks to many individuals and organisations that Court 15 is now the wonderful museum it is today. The rescue campaign was launched in 2001 and received national attention. It appeared that the fate of a block of back to backs in central Birmingham touched the heart of the nation, and that everyone seemed to have had a parent or a grandparent who had once lived in one.

The largest grants came from the Heritage Lottery Fund (£1,000,000) and from the European Regional Development Fund (£300,000). Many people sent sums of money both large and small, the letters attached to the cheques all said the same thing. That Court 15 was too important to be allowed to crumble away, and that its history was our history.

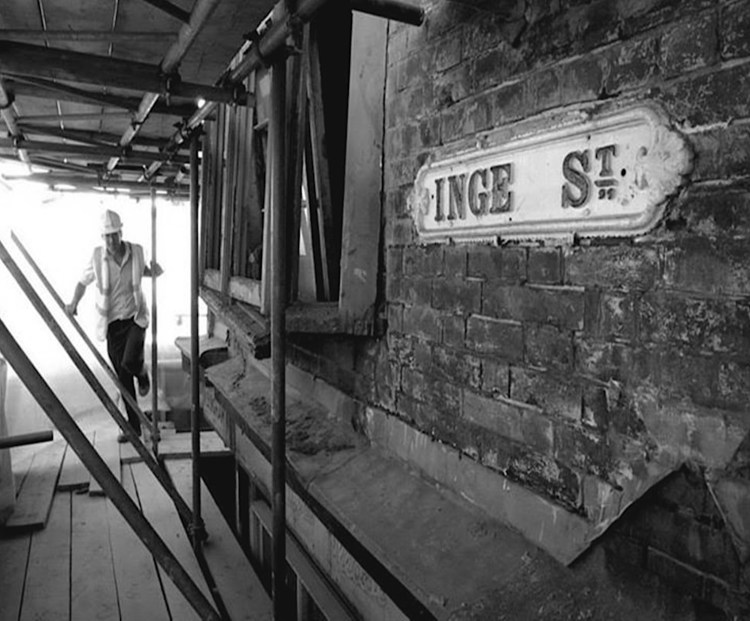

It was in the 11th hour for the buildings, which had to be supported by scaffolding to prevent their collapse. Thanks to those grants and donations, Birmingham Conservation Trust were able to begin the £1.5m. restoration programme. Local contractors, with special conservation skills, William Sapcote & Sons, were used to carry out the renovation work. Birmingham Conservation Trust was responsible for the capital funding for the project and the implementation of the building repairs. Once the building work was completed the National Trust took over the buildings and was responsible for opening Court 15 to the public in July 2004.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs Restoration – THEN

Work on the chimney stacks

Replacing a window frame in Inge Street

Work in progress around the Courtyard

Extensive scaffolding surrounding the houses

The Back to Back houses near to completion

The restoration finished, awaiting the opening

Birmingham Back to Backs The Courtyard

House number 1 & 2 before restoration

House number 1 & 2 after restoration

The wash house (Brew’us) before restoration

The wash house (Brew’us) after restoration

House numbers 2&3 before restoration with Pauline Meakin in the entry

House numbers 2&3 after restoration

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs – THEN & NOW in Hurst Street

The corner of Hurst Street and Inge street c1984

The corner of Hurst Street and Inge street 2018

Hurst Street side before restoration

Hurst Street side after restoration

Hurst Street in 1953

Hurst Street in 2020

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs – The Properties & The Families

At the time of writing Birmingham Back to Backs have enjoyed fifteen hugely successful years, attracting thousands of highly satisfied customers each year (2004-2019). To ensure the smooth running of the property there is a small amount of permanent staff, supported by a number of part time staff. By far the largest workforce are the volunteers, numbering over 150 dedicated and passionate people. Their roles range from Booking Line Assistant, Visitor Reception Assistant, Atmospheres Set-Up Assistant, Tour Guides, Conservation Assistant and Education Assistant, without their support and knowledge the Back to Back Houses would not exist.

A visit to Birmingham Back to Back consists of a guided tour of the restored properties in the courtyard offering a fascinating trip back in time to the daily life of four families in 1840’s, 1870’s, 1930‘s and the 1970’s. Furniture, objects, silverware, costume and most of all memories vividly bring these periods back to life, evoking a bygone Birmingham. Interactive exhibits allow visitors to learn more about the past so often seemingly long vanished.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Levy House

The first house visited in Court 15 is number one, depicting life in the 1840’s. The family living here at that time are a Jewish family consisting of husband, Lawrence Levy his wife Priscilla and their four children Joseph, Adelaide, Morris and Emanuel. Lawrence was a skilled man, his trade is the manufacture of decorative clocks hands. In Birmingham at that time there were thousands of highly skilled men and women producing high quality, fashionable artefacts, jewellery, timepieces, buttons, buckles, snuff boxes, silver ware, mother of pearl items, these people were mainly based in the Hockley area of the city, known as the Jewellery Quarter. The generic name for artisans working in these particular trades was a “toy maker”.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Oldfield House

The next house is set in the mid Victorian (1870’s) period. The residents are, Herbert Oldfield, wife Annie with their large family they also have living in the house two lodgers!. Privacy was not important, what was, is paying the rent at the end of the week, the lodgers would contribute to that necessity. Herbert, was another skilled man who traded from home, working in glass. He made the usual glass orna- ments but his main trade was the manufacture of glass eyes, for stuffed animals, dolls, teddy bears and also for humans. The average life span of a working man in Birmingham was approximately 25 years-35years, Herbert died in Birming- ham Workhouse Infirmary from Dementia and Exhaustion!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

The Mitchell House

The third house portrays the 20th Century (1930’s), featuring the Mitchell family, who occupied the same house in Court 15 for 95 years, across three generations, Grandfather Thomas, son Benjamin, and his son George. The story in this house relates to George Mitchell the last connection with the family and the courtyard. The Mitchells were bellhangers and locksmiths. Birmingham in the 19th century was spreading outwards into the new suburbs and many churches were being built, needing bells and locks and this is how the three generations of Mitchells earned a living. They would have been producing locks, keys and other metal objects from their small workshop which was situated in the courtyard above the washhouses. As far as it is known all of George’s life was based around Court 15, his workshop and his back to back house. Certainly all of his adult life George lived a bachelors existence alone in his home, with his parents passing on and his siblings leaving the court, but living in a back to back court you are never really alone. George died in 1935 at the age of 70 in Court 15. One may have thought that George did not have much money to his name – living as he did in a run down back to back, so why did he not move on elsewhere? His parents did, they moved to a nice house in leafy Edgbaston and may even have had a servant. But George would have enjoyed the sense of community that he found in Court 15.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

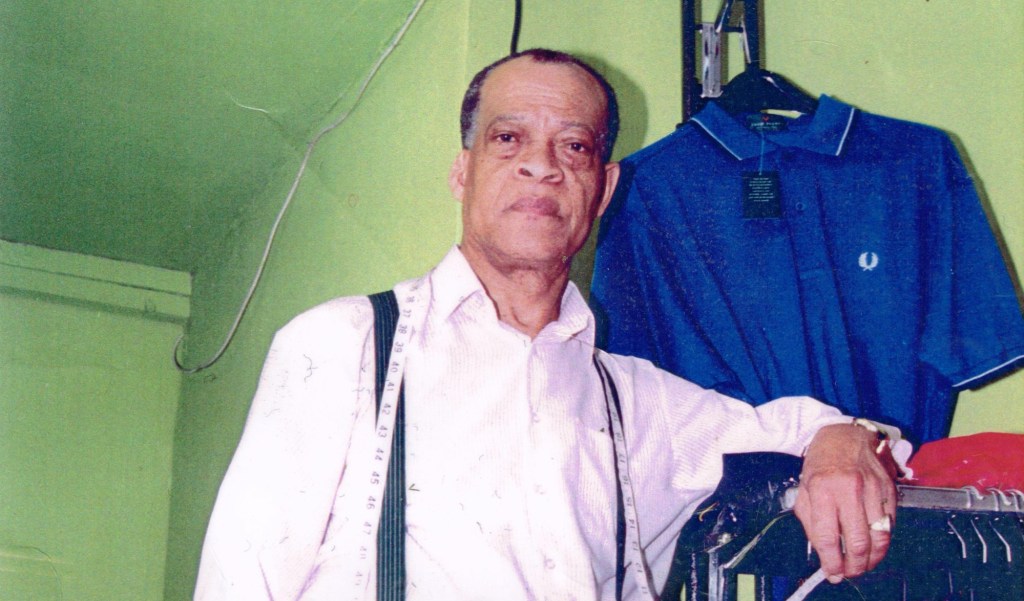

George Saunders Tailors Shop

The final visit is not to a residential home, but to the business property of George Saunders, a tailor. George had the honour of being the last person to work in Court 15 and the very last person to leave with the courts closure in 2001. George Saunders came from St Kitts in the West Indies, making the journey in 1958. It was not easy to find work in those early days, mainly due to discrimination. George took on many menial jobs, one of them was working in a biscuit factory in Small Heath. During this time George was always saving money to put on a deposit for his own business. He worked for a well known tailor called

Philip Collier before setting up in business on his own in Bordesley Green. He moved into 61-63 Hurst street in 1974, hoping to get work from the Hippodrome across the road, but by then they had their own tailors. George was surprised to find Hurst Street was Birmingham’s Savile Row, with an abundance of predominantly Jewish tailors plying their trade the whole length of the street. George Saunders built up his reputation mainly in the Caribbean population of Birmingham, and his customer base was by word of mouth. In the 1980’s Georges son Clifford who was also a tailor joined him in the premises next door. With a lot of museums that open in former workshops, you get the sense that some of it has been modified by the restoration team, or at least moved to a place where the inquisitive tourist might see it better. Not so with George Saunders former tailors shop. It has been meticulously preserved by The National Trust to the point that it feels like George is just off on his lunch break. Nothing has been changed within the building, and everything is laid exactly where it was when George practiced his trade. On retirement he did not take with him as much as a single button!

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs – The Wash-House

There was two kinds of buildings that occupied one side of the courtyard. First there was the wash house, colloquially known in Birmingham as the “brew house” or “brew-us” and the other building was usually taken up by the “privies” or lavatories.

The washing of clothes was a ritual that remained practically unchanged for the best part of two centuries. Early in the morning cold water had to be carried from the well (in this case the Lady Well) or across the courtyard from the stand pipe or pump in order to fill the boiler or “copper”. This large cast-iron or copper container was encased in blue brick which helped to insulate it. Underneath the copper was a grate where a fire was started to heat the water. The washing was boiled and agitated using a metal “posser” (or “posher” – depending how “posh” you were), repeating the process several times. After boiling, scrubbing on the galvanized wash board and starching, the washing could be removed from the copper and transferred to a “maidening tub” , where a wooden “dolly-maid” would be employed to get rid of the soap and to rinse the clothes in clean water. The “dolly maid” was a fat wooden rod, with a cross-bar handle at one end and a circular lump at the other end. The wood was notched out, so that it resembled a miniature castle top in reverse. The implement was then dropped onto the tub, heavy end first, and twisted, twirled, bumped and spun round till the soap was rinsed out of the clothes.

The wet clothes are then fed through a mangle or wringer which squeezes out the excess water, before the clothes were swilled out again, put through the mangle once more and finally hung out on a washing line strung up across the yard. The whole procedure could take all day and was extremely arduous and back breaking work.

Back to back courts at the end of the 19th and into the 20th century were usually managed by a matriarch woman. This woman’s Mother and possibly her Grandmother were matriarch’s, they would live in the best house in the court, they may have had a small garden, because no-one said they couldn’t . The landlords loved these ladies because the kept some sort of order in the courts. There were many un-written rules which everyone had to adhere to, due to living in close proximity to one and other. For instance she would allocate the days or times for your wash to take place, based on length of time residing in the court, the newcomer would be right at the bottom of the “pecking order”.

Washing in a back to back living room

Hanging out the washing in a Hurst Street courtyard

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs – The Privies

Next to the washhouse in Court 15 are the “privies” consisting of two toilets set in different eras. The first is a “dry toilet set in approximately the 1840s and the other is a flush or wet toilet set in the 1930’s.

In the Middle Ages toilets were simply pits in the ground with wooden seats over them. However in the Middle Ages monks built stone or wooden lavatories over rivers. At Portchester Castle in the 12th century monks built stone chutes leading to the sea. When the tide went in and out it would flush away the sewage.

In Medieval castles the toilet was called a garderobe and it was simply a vertical shaft with a stone seat at the top. Some garderobes emptied into the moat. In the later Middle Ages some towns in Europe had public toilets. By the Middle Ages wealthy people might use rags to wipe their behinds. Ordinary people often used a plant called common mullein or woolly mullein. When the Roman soldiers were based in Britain about 2000 years ago they had sophisticated communal toilets and used a rag on a the end of a length of wood. Was this where (jokingly) the term “pooh-sticks” came from?

In 1596 Sir John Harrington invented a flushing lavatory with a cistern. However the idea failed to catch on. People continued to use chamber pots or cess-pits, which were cleaned by men called gong farmers. (In the 16th century a toilet was called a jakes). However in 1775 Alexander Cumming was granted a patent for a flushing lavatory. Joseph Bramah made a better design in 1778. Thomas Crapper did not invent the flushing toilet that is a historical myth, he manufactured them and created a very successful company selling urinals and flush toilets. The Stratford-upon-Avon based company still makes Victorian styled sanitary-ware at their factory in Huddersfield.

However flushing toilets were a luxury at first and their use did not become widespread until the late 19th century. In the 19th century were earth closets were more common. An earth closet was a box of granulated clay over a pan. When you pulled lever clay covered the contents of the pan. In rural areas flushing lavatories did not replace earth closets until the early 20th century. In the early 19th century working class homes often did not have their own toilet and had to share one. Sometimes you had to queue to use it.

Toilets in a back to back court were normally shared by the residents, approximately one WC to every four or five houses, until the 1930’s where it was on WC for every two houses. The toilets always kept locked with each house having its own key. In the first half of the 19th Century toilets were predominately dry and called “earth closets”. In Birmingham courts there was usually a rubbish area called a “miskins”, normally a low walled area on the corner of the court where the human waste was thrown and overlain with ashes. These waste areas were emptied by private contractors called night-soil men and the contents sold on to farmers as manure. Instead of a fenced area some courts or houses may have had a metal barrel to pour the waste into along with anything else that could not be burned. The word miskin was applied to this barrel as well and the term was adopted for dustbins well into the 1960s.

Up until the 1870’s when piped water became available the privies were often fitted with what is known as a “pan-closet”. This metal pan or pail was installed under the seat and offered what was called “Closet accommodation” for around a week, after which it was collected by the night soil men and a fresh pan left in its place. Birmingham adopted this system in 1874, as part of a wider initiative in waste disposal. It was not until the end of the 19th century that flush toilets were gradually replacing the old dry toilets. It may have taken approximately 75 years for a city the size of Birmingham, for all residents to have access to a flush toilet.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs – The Sweet Shop

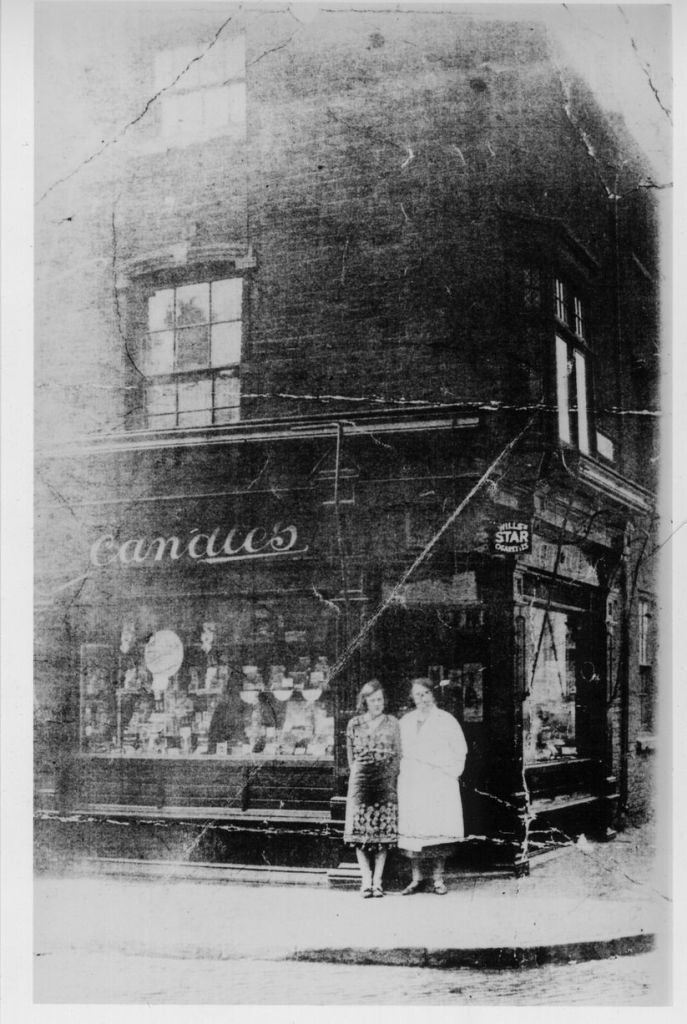

There has been a confectioner’s at 55 Hurst Street from the early years of the last century, this after all was Birmingham’s theatre district where the patrons of the Hippodrome could purchase their sweets prior to enjoying the upcoming variety performance.

By 1910 the sweet shop was being run by Francis Dibble, and by 1930 it was occupied by a James Hurley, having gone through a string of different tenants in the years between. The sweet shop on the corner of Hurst Street and Inge Street was synonymous with Arthur Bingham, who took over in 1936 and was still there well into the 1960’s. After Arthur Bingham retired in 1966 the shop was taken over by Mr Xendides, a Greek Cypriot. Arthur Bingham’s bills and receipt from the 1960’s contained orders for a vast array of old fashioned sweets. This was the place to come for sherbet fingers, treacle mints, blackcurrant and aniseed drops, fruit salad and gold butter caramels. There were sour fruits and acid drops, plush nuggets and banana splits, melba fruits and barley sugars. Mr Bingham also stocked troach drops, menthol, eucalyptus and bronchial pastels. These were possibly sold to give comfort to the smokers who along with their sweets they could also purchase cigarettes, Woodbines, Players and Capstan Full Strength.

From around the 1980s until the end of 1990’s the corner shop became “Oscars”. The trend for take-away food was growing beyond the usual fish & chip shop. In fact by the 1980s there was a fish & chip shop next door, imaginatively called ….. “The Chippy”! Oscars was a Kebab shop plying its trade for the Hippodrome customers and those frequenting the bars and clubs springing up in the area.

From the opening of The Back to Backs by the National Trust in 2004 until 2010 all the old fashioned sweets were being sold (with more modern ingredients) in a reincarnation of “Arthur Bingham’s sweet shop”.

Rose Bingham and her mother, Florence Wiggett outside the sweetshop at 55 Hurst Street in 1936

Candies sweet shop at 55 Hurst Street – 2019

Arthur Bingham in his sweet shop – 1939

John Bingham (Arthur’s son) at the NT’s Back to Backs sweet shop in 2004

The old fashioned cash register in the sweet shop

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Birmingham Back to Backs – An Unfortunate Death

Let’s take a look now at an unfortunate death that took place near to the corner of Hurst Street and Inge Street some 80 years ago.

We’re going back to 1939 when the occupant of the shop to the left of the corner shop seen above, was John Hunt, selling books and newspapers.

John did not live there, his mother Marie, aged 59, and his sister Hilda, 18, lived above the shop. The first floor was their living room, and the attic was their bedroom. Later events made it clear that the two women would habitually change into their nightclothes in the living room, which would have been kept warm by a gas fire, before making their way up to bed.

On the 24th of May 1939 the pair went up to bed as usual and they were woken in the morning by shouting in the street. Workmen walking past saw smoke pouring from the first-floor window above the shop, then the two women appeared at the attic window, shouting for help.

A passer-by told the newspapers “There were not many people about, but within a few minutes about 20 of us were trying to rescue the women. Someone kicked open the door of the shop and tried to get up the stairs. But the room above the shop was a mass of flames, and it was impossible to get through. We got a ladder, but found it was too short to reach the window, so several of us raised it and the young woman, in her pyjamas, climbed down. The mother tried to get out of the window, but couldn’t so she went back into the room”.

It turned out that Mrs Hunt weighed 15 or 16 stone, and it seems that she was not able to get through the tiny attic window. The fire had spread up the staircase, cutting off escape except through the window. Medical evidence was that Mrs Hunt had burns involving her whole body.

The newspapers reported that a bus came along, and the driver was asked to put it on the pavement, so that the ladder could be taken from the top deck to the window. Someone ran up the bus stairs and opened the window, but then the Fire Brigade arrived, and the bus had to be moved so that the firemen could take over. The firemen beat a way through the flames and smoke and brought out Mrs Hunt, who was taken to the General Hospital.

The first-floor room was almost destroyed. Fire appears to have broken out in this room, trapping the women in the attic above, and the only way out was by the narrow stairway.

District Officer Percy West, of the Birmingham Fire Brigade, said “It was impossible to get up the bedroom stairs owing to the heat. Eventually the old lady was found on the bed.” The fire, he believed, originated in the living room. He continued, “It is a tragic thing, that untrained people open doors and windows and thus make a flue for the fire. Had the door been closed and kept closed, there would have been quite a possibility of saving Mrs Hunt.”

You’d think that John Hunt would close his business after loss of his mother, but he continued to run his newsagents shop until 1945 when it was taken over by a Jewish refugee called Mannie Gorfunkle. It was said that Mannie would scare the local children, because had an alarming twitch bought on by the treatment he received at the hands of the Nazis.

We know that a tailor called George subsequently used the shop for his business and he must have chosen the attic as a fitting room. Being at the top of the building there was more daylight than at street level. George had attached mirrors to the walls, but he discovered that each time he fitted a mirror it would, within a few days, crack.

Doesn’t it make you wonder if Marie Hunt had anything to do with this unusual phenomenon? The tailor in question was George Saunders and you’ll know, of course, what these buildings are. If you have been on a guided tour of the Back to Backs you may have stood in the rooms where Marie Hunt once lived and died.

[Note: Marie Hunt was 59 years old. In his report, District Officer Percy West, of the Birmingham Fire Brigade, said “… the OLD lady was found on the bed …..”. We think that he would not be very popular if he said that today!!]