Hurst Street at Work

The sounds we can hear in Hurst Street echo those other streets in Birmingham and countless other towns and cities. What we cannot hear we can reconstruct, using written records, census, maps and photographs

Hurst Street during the day is a fairly quiet thoroughfare, with only the Hippodrome theatre crowd attending the afternoon matinees bringing a lively atmosphere to that immediate area. Shoppers no longer venture as far as Hurst street, preferring the large shopping malls in the centre of the town. When night falls Hurst Street comes to life, the Hippodrome opens its doors, as do the many restaurants and eating places of varying ethnicities, the overriding aroma of the area is of Tandoori Chicken and Thai Green Curry, the Gay pubs and bars complete with each other for volume of sound and custom.

Entertainment and culinary activities were not always the life blood of the famous street. During the 18th and 19th century’s Hurst Street consisted of many workplaces and shops and also numerous back houses where these highly skilled men and women lived, many living over their place of work. With many Jewish immigrants settling in the area, tailoring was a predominate trade as was “toymaking”.

Birmingham had a long tradition of metalworking. The proximity of good supplies of coal and iron ore, together with the increase in demand for luxury goods contributed to the growth and development of metal industries during the eighteenth century. Birmingham specialised in producing small decorative metal wares known as “toys”. This term included a multitude of goods made in steel, brass, iron, gold and silver as well as other materials.

The two most important branches of toy trades, were buckle and button trades both catering for a fashion-conscious market. By 1760 it was estimated that in Birmingham around eight thousand people were employed in making buckles, and that business generated £300,000 worth of trade. During the second half of the century the production of buttons helped to secure Birmingham’s international reputation as the world’s leading button-making centre.

The toy industry grew in importance through the eighteenth century. By 1759 it was estimated that twenty thousand people worked in these trades in Birmingham . Toy workers in and around the city centre worked from small workshops, where all members of the family were involved. There were many of these small establishments in Hurst Street highlighting another important aspect of Birmingham’s toy trades – the subdivision of labour.

Here’s a list of the wide variety of manufacturing trades that could have been found in Hurst Street that got listed in trade directories in the first half of the 20th century. It is most likely that other trades were being carried out in back rooms and attics that never got listed.

| Cap Maker | Boot & Shoe Maker |

| Slipper Maker | Bookbinder |

| Carriage Lamp Manufacturers | Stone Carver |

| Whip Thong Maker | Watchmaker |

| Glass Tablet Manufacturers | Fancy Leather Goods Manufacturers |

| Saddle Tree Maker | Cardboard Box Manufacturers |

| Cycle Saddle Makers | Feather Dresser |

| Electroplater | Pocket Book Maker |

| Coach Builder | Oxy-acetylene Plant Manufacturers |

| Piston Manufacturers | Bag Frame Manufacturers |

| Riddle Maker | Screw Manufacturers |

| Pattern Makers | Automatic Machine Maker |

| Aluminium Hollowware Manufacturer | Electric Heating Apparatus Manufacturing |

| Cycle Enamellers | Nail Manufacturers |

| Brass Founders | Manufacturing Optician |

Working in the top bedroom of his back to back house in Court 15, Hurst Street, Lawrence Levy , a Jewish toymaker produced decorative clock hands. He would then pass his wares to the next artisan who would attach the hands to the clock faces, the next person, the numbers, the next the bezels, this process may involve several individual toymakers to manufacture a luxury item such as a large clock. Skilled workers concentrated on producing individual parts or an object and often did not see the completed article.

This is a photograph of Mr Levy’s work bench known as a “Jewellers Peg”, if possible the bench would be situated next to the main source of daylight. The “peg” is the wooden protrusion projecting from the centre of the bench.

Arranged on top are his tools of his trade, including drills, cutting tools, a selection of hammers and a miniature vice. Amongst the tools on the bench are an “Archimedes Drill” which uses an Archimedes screw to turn the drill bit by moving the plunger up and down the stem. There is also a “Bow String Drill”, which is also attributed to Archimedes. These drills were not invented by Archimedes but because the way in which the drills work is based upon the Archimedes screw principle. These drills are still used today by many jewellers and in other trades.

A visitor to Birmingham in the 1750’s noted it took seventy people to make a button, with each person involved in a different process.

The enormous variety of metalworking skills employed in the toy trades helped to make Birmingham craftsmen supremely adaptable. When for example, in the 1790’s, the fashion for wearing shoe buckles waned in favour of shoe laces many buckle makers transferred their skills to producing buttons and jewellery. This was the foundation of the jewellery trade, which by the mid-nineteenth century had become one of the most important industries in Birmingham, again situated in Hurst street at that time were several jewellery workshops.

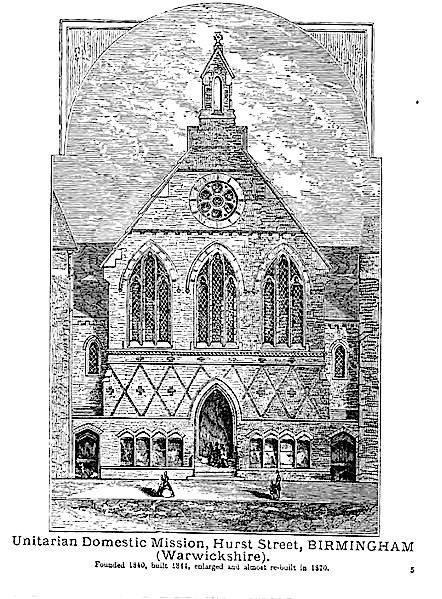

The Unitarian Association for the Midland Counties built a chapel known as the Hurst Street Domestic Mission on Hurst Street in 1844. It had schoolrooms beneath the chapel, and additional schoolrooms to the rear were added later. Its large central room became known as the People’s Hall, were the working people, of all denominations could attend free lectures. The school’s efforts to educate the city’s poorest children were praised by the Inspector of Schools in the 1850’s.

The poet, Robert Southley christened Birmingham as “a city of a thousand trades”, he was not exaggerating, in fact it was an underestimation. In 1849 it was estimated that Birmingham had 2,600 trades and many of these were evident in Hurst Street during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. They range from The Gun Trade, Button Making, The Jewellery Trade, The Leather Trade, Bell Founding, Lock Manufacture, The Brass Trade, Plated Wares, Wire Working, Iron Bedstead Makers, Paper Mache & Japanning, Glass Working, and many more. As late as 1900 there were workshops in Hurst Street making prams, horse brasses, carriage lamps, whips, watch-cases, shirts, waterpipes and bicycles.

During the 20th century most of these trades had disappeared with the advent of mass production taking place in Birmingham. Hurst Street slowly transformed from predominantly a manufacturing street to a retail thoroughfare with the usual butchers, greengrocers and bakeries, but many of the outlets were tailors shops with the majority of proprietors being Jewish immigrants. In fact Hurst Street was known as “The Savile Row of Birmingham”. Obviously it was not as upmarket as its London counterpart and certainly not as expensive, but for the well dressed Birmingham male there was plenty of tailors to choose from. Ironically the last tailor to leave Hurst Street was not Jewish but from the Caribbean, he was George Saunders who occupied a shop near the corner of Hurst Street and Inge Street from 1974 to 2000.

Today Birmingham is the most multiracial city in the UK, but that was already becoming the case by the middle of the middle of the 19th century with Hurst Street reflecting this trend. Living in Hurst Street at that time were migrants from southern Italy, Russia, Poland and the south of Ireland. Many residents of Hurst Street were migrating from Wales and from the rural counties around the West Midlands. In more recent years they have come from further afield, from the West Indies, the Asian subcontinent and the vast majority in the Hurst Street area have come from Hong Kong.

We’re now going to continue our journey from Hurst Street into Ladywell Walk.